Sibling Contact After Adoption: The Pros and Cons of Staying Connected

When children are adopted into different families, one of the most emotionally complex questions that arises is whether — and how — siblings should remain in contact. These days adopted children have access to a lot of information about their biological families, and are encouraged to have contact with any siblings they may have, whether full siblings or half siblings. But maintaining these relationships can bring challenges that need careful thought and sensitive support by the adoptive parents on both sides. Contact can be destabilising for some children. How do children who have already experienced early, unwanted, separation from their biological mother and sibling/s, make sense of contact with a sibling/s in a different family to their (adoptive) family?

So what are the potential benefits and difficulties of sibling contact for these children?

Why Sibling Relationships Matter

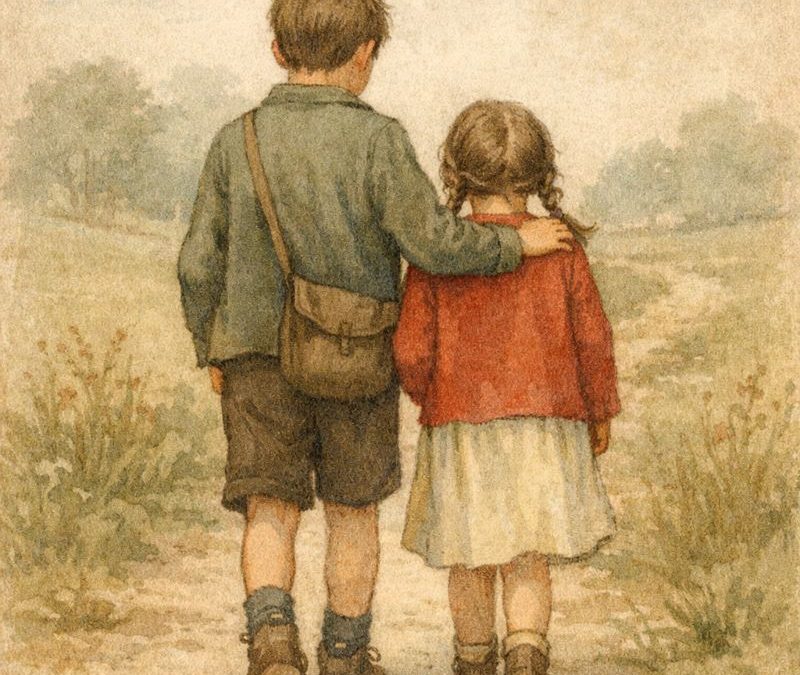

Sibling relationships are often among the longest-lasting connections in a person’s life. But for children who have experienced early loss, brothers and sisters may represent continuity — someone who “knew me then”, ‘someone who shares my loss”.

From a psychoanalytic perspective, early sibling bonds can hold powerful emotional meaning, even when children have limited words to describe what they feel. When siblings are separated through adoption, the loss of these relationships may be carried quietly in the child’s inner world. This can emerge later as sadness, anxiety, anger, or a sense of something missing — experiences frequently explored in psychotherapy with adults who were adopted as babies or young children.

The Potential Benefits of Ongoing Sibling Contact

Maintaining contact between siblings adopted into different families can offer important emotional benefits when it is carefully thought about and well supported.

Emotional continuity and identity

Ongoing sibling contact can help children retain a connection to their origins and shared history. This can support the development of a more coherent sense of self, particularly as children grow older and naturally begin to ask questions about who they are and where they come from. These identity questions often feature in psychotherapy.

Shared understanding

Siblings who lived through similar early experiences may offer one another a unique form of recognition. Even occasional contact can carry the quiet reassurance that someone else remembers the same beginnings, reducing feelings of isolation that are usually associated with adoption.

Reassurance and belonging

For some children, sibling contact can soften unconscious fears linked to separation and abandonment. Knowing a sibling exists can bring a sense of belonging, and of a sense of identity.

The Emotional Complexities and Challenges

While sibling contact is often experienced as meaningful, it can also stir complicated and sometimes conflicting feelings.

Re-awakening loss and grief

Contact may remind children of what they have lost — shared homes, shared carers, or a time before separation. Some children appear unsettled after contact, because it brings up painful emotions that they may not have the maturity to process. These responses are often misunderstood and can benefit from therapeutic understanding.

Differences between adoptive families

Children may notice differences between families — routines, boundaries, lifestyles, or opportunities. These observations can give rise to confusion, envy, or questions about fairness, which may be difficult for children to express openly.

Changing wishes over time

A child’s feelings about sibling contact are not fixed. What feels manageable and helpful at one developmental stage may feel overwhelming at another. Contact arrangements need to remain flexible and responsive to the child’s emotional development.

Why Quality Matters More Than Frequency

Perhaps it is not whether siblings remain in contact, but how that contact is experienced emotionally.

Contact is more likely to be supportive when it feels safe, predictable, and thoughtfully held by the adults around the child. From a psychodynamic perspective, attention is paid not only to the contact itself, but to its emotional meaning — what it represents to the child, what feelings it stirs up, and how those feelings are understood before and after contact takes place.

The Role of the Child’s Adoptive Family

Ongoing sibling contact relies heavily on the adults involved. This often includes two sets of adoptive parents, and sometimes professionals.

Anger towards the adoptive family is not uncommon and it is highly likely that knowledge of and furthermore contact with the biological family may well heighten this, as the child is faced with their painful past in their present. It is a reminder of their loss. They may have fantasies of what life with their biological family would have been, as good, and compare their adopted family with this. Unless handled sensitively it could destabilise the adopted family unit. With the best intentions adoptive parents may overlook what is in fact best for the child. Therefore contact with biological siblings is a serious matter.

In turn adoptive parents may find that sibling contact stirs their own feelings, such as protectiveness, anxiety, uncertainty, or fears about destabilising their child. Loss of their ability to have their own biological family may surface, and they may wonder what their own biological children would have been like. Feelings that are unique to parents that were unable to have their own biological children. These responses are entirely understandable and they can be supported in psychotherapy.

A Psychoanalytic Perspective

From a psychoanalytic psychotherapy perspective, it can be helpful to think about the child’s inner world, the impact of early loss, attachment patterns, and the potential for identity issues. When these dynamics are kept in mind, sibling contact — whether frequent, occasional, or indirect — can be managed in a way that supports emotional development.

An Invitation

If you are an adoptive parent, or an adult adoptee thinking about sibling relationships, or adoptive parents you may find that these questions stir strong and conflicting emotions. Exploring them in a therapeutic space can help bring clarity and understanding to what lies beneath the surface — including feelings of loss, loyalty, belonging and identity.

You can read more about my work as a psychoanalytic psychotherapist working with adoption and early relational experiences on my

<a href=”https://www.drkimberleycarter.co.uk/adoption/”>Adoption</a> page, and how psychotherapy can offer a steady, reflective space to think about these issues in depth.

Recent Comments